“What is research, but a blind date with knowledge?” – Will Henry

As an English major, one of the questions I hear most often is: “What do you plan to do with your major?” and other variations of “What do you want to do with your life?” These well-meaning skeptics tend to appear in the form of Asians, pre-professional majors, and engineers. At Thanksgiving gatherings with family friends, I get either the sympathetic stares reserved for “Girl-Destined-To-Live-In-A-Cardboard-Box” or eager suggestions for me to go to law school or switch to business. It seems to me that most people look at college as more of a vocational school than a center of knowledge and exploration, intended to advance our understanding of the world we live in and acquaint ourselves with the greatest minds of human history.

Of course practical preparation for the real world is important. There’s no doubt that necessity and therefore money is a powerful motivating force. But I can’t help but think that there’s something more to life than “bread and butter.” Like the ascetics of Buddhism, I tend to believe that materialism and physical needs are paltry compared to our spiritual well-being and somehow, even though I understand the benefits, I can’t bring myself to forsake my intellectual interests for a bigger wallet (not that I’m against money in general – if you happen to love a subject that also brings in the big bucks, more power to you).

However, despite the inconveniences of always having to defend my major, I do think that it is a valid question. Why literature? Why research? Why academia? There seems to be a strain of anti-intellectualism in America that discourages the life of the mind, the pursuit of the Ivory Tower. The common thought is that spending too much time in scholarly endeavors renders one useless in the actual society, but personally, I think this is an unfair stereotype. I don’t think there is anything more pure and beautiful than the pursuit of knowledge and truth.

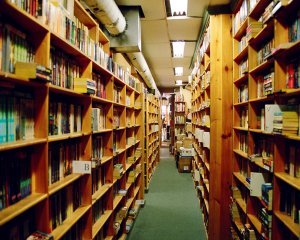

A couple weeks ago, I bought a stack of books from an English Department book sale, one of which being The Art of Literary Research by Richard D. Altick (1975). The pages are yellowed and the book has that old library smell, but I like flipping through it whenever I’m having an academia-induced anxiety attack. One quote at the very beginning of the book I think sums up the attraction of studying literature:

“In no other subject is the pupil brought more immediately and continuously into contact with original sources, the actual material of his study. In no other subject is he so able and so bound to make his own selection of the material he wishes to discuss, or able so confidently to check the statements of authorities against the documents on which they are based. No other study involves him so necessarily in ancillary disciplines. Most important of all, no other study touches his own life at so many points and more illuminates the world of his own daily experience” – Helen Gardner, “The Academic Study of English Literature,” Critical Quarterly, I (1959).

These factors led me to the study of literature and they are also what keeps me here. I’ve been given advice to just fulfill my intellectual curiosity in college and then go out and get “a real job,” but I don’t really see how I can do that. You can’t really satisfy a thirst for learning in four meager years, or even in a lifetime. In the final (and my favorite) chapter, Altick describes “The Scholar’s Life” and every time I read it, I’m reminded of why I want to spend my life in academia.

“The scholar really never ceases being a scholar. He may firmly lock his office door at the end of the day, but he never locks or sequesters his intellect. Consciously or subconsciously he continues to mull over the problems his restless curiosity about books and history has set loose in his mind, and sometimes, at the oddest moments – at 3 A.M. or while taking a shower – a bright new idea may come to him from nowhere… The bookish excitement that has led them into the profession permeates their lives.”

“No other profession offers so legitimate an excuse for reading great literature. And though the siren song of research may lead us to spend many hours in realms far removed from art, if we learn our lesson correctly, they may sharpen our understanding and appreciation of the masterpieces to which we are devoted.”

“Though time is always short, we have the lifelong company of books; and what is more, we have good human companionship… Love of books and a consuming interest in the intellectual and esthetic questions they pose make brothers of men with amazingly different backgrounds and tastes. In scholarship there is no prejudice born of national origin, creed, color, or social class; we live in the truest democracy of all, the democracy of the intellect.”

I’m willing to concede that Altick’s portrayal of a career in literary scholarship may be a bit idealized, but I think its a beautiful ideal to aspire to. At its best, research can be infinitely rewarding.

(Clearly, I have not been disillusioned yet.)

On a final note: Who else is really depressed about Pushing Daisies being cancelled? Let’s mope together with some pie (dosed with homeopathic mood-enhancers), knitting, and pop-up books. 😦

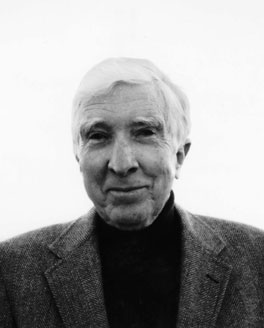

I, Sophia Literaria, was in the same room with a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner (I’m actually pretty sure this is the first time this has happened… unless I unknowingly met one during the LA Festival of Books last year).

I, Sophia Literaria, was in the same room with a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner (I’m actually pretty sure this is the first time this has happened… unless I unknowingly met one during the LA Festival of Books last year).